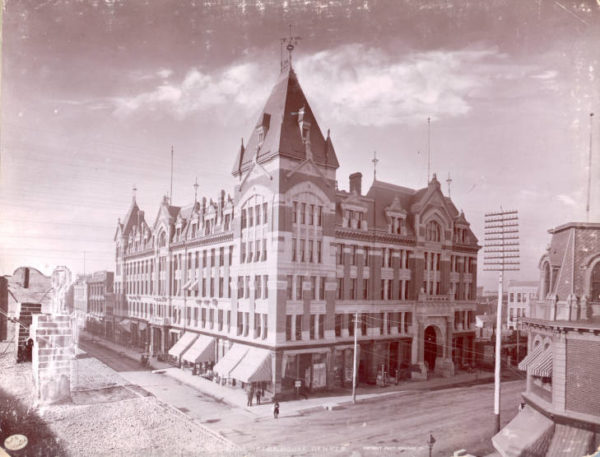

139 years ago this week, on September 5, 1881, occurred what was arguably the most anticipated event in Denver’s history up to that time — the lavish opening night of the incredible Tabor Grand Opera House. Financed by mining millionaire Horace Tabor, the opera house is considered by many to be among the finest buildings ever constructed in Denver — and one of the greatest losses.

Horace Tabor had already built an opera house in Leadville, but soon set his sights on Denver. He purchased land at the corner of 16th and Curtis downtown and sent for noted Chicago architect brothers Willoughby and Frank Edbrooke to design a opera house on a far grander scale than Leadville’s. The resulting edifice cost the enormous sum of $800,000 to build. That’s equivalent to $20.3 million today. It was the most expensive building constructed in Denver up to that time and remained so for many years to come. On the exterior, which featured a huge corner tower, red brick and white Manitou limestone alternated to create a striking multi-color effect. Inside, marble stairs led to a 1,550-seat auditorium crowned by a glistening crystal chandelier and a ceiling painted in the colors of the sunset. Stained glass windows, intricate woodwork, and plush furnishings added to the building’s elegance. In addition to the main auditorium, the building also featured office space, a drama school, a barber shop, and a saloon. Architect Frank Edbrooke would have his office there, going on to design some of Denver’s most significant buildings such as the Brown Palace Hotel and supervise completion of the State Capitol.

In anticipation of opening night, Denver’s newspapers ran articles with instructions on proper theater etiquette. Railroads scheduled special excursion trains, and visitors poured into the city to witness the spectacle. Attendees were handed programs made of perfumed silk, and the night’s featured performer was world-famous soprano Emma Abbott. Also that night, Horace Tabor was presented with a solid gold watch fob in the shape of an ore bucket, paid for by citizens in gratitude for the millionaire’s gift to the city.

The Tabor Grand’s glory days would only last for about a decade, however. By the early 1890s, numerous other theaters were being constructed in Denver, including the elaborate Broadway Theater. After a few more years, a new pastime, movies, swept the nation. The Tabor was converted to a movie palace but it never really took off. In the 1920s a proposal was set forth to demolish the outdated structure, but it managed to hang on another forty years. Finally, in 1964, a development company purchased the building for less money than it had cost to build, and one of the grandest buildings in the history of Denver was reduced to rubble. In its place was constructed the Brutalist-style Federal Reserve Bank, which occupies the site today. When the opera house opened, however, a poem that appeared on the stage curtain proved to be prophetic:

So fleet the works of men,

Back to the earth again.

Ancient and holy things fade like a dream.

The Tabor Grand Opera House and its opening were such significant parts of Denver’s story that they have been featured prominently in numerous publications. Readers interested in learning more about Horace Tabor, the Tabor Grand, and Denver’s performing arts history can check out from our library such titles as Horace Tabor: The Life and the Legend; The Tabor Story; and Orpheus in the Wilderness: A History of Music in Denver, 1860-1925. The Tabor Grand is also profiled in the State Historical Society’s 1927 History of Colorado as well as in the March 1941 issue of Colorado Magazine. Colorado Virtual Library also features biographies of Horace Tabor, his first wife, Augusta Tabor, and his second wife, Baby Doe. An article about the Tabor Grand Opera House also appears in the Colorado Encyclopedia.

The Tabor Grand Opera House and its opening were such significant parts of Denver’s story that they have been featured prominently in numerous publications. Readers interested in learning more about Horace Tabor, the Tabor Grand, and Denver’s performing arts history can check out from our library such titles as Horace Tabor: The Life and the Legend; The Tabor Story; and Orpheus in the Wilderness: A History of Music in Denver, 1860-1925. The Tabor Grand is also profiled in the State Historical Society’s 1927 History of Colorado as well as in the March 1941 issue of Colorado Magazine. Colorado Virtual Library also features biographies of Horace Tabor, his first wife, Augusta Tabor, and his second wife, Baby Doe. An article about the Tabor Grand Opera House also appears in the Colorado Encyclopedia.

Although Denver’s opera house is long gone, the Tabor Opera House in Leadville still stands. This opera house was also profiled in Colorado Magazine, in a 1936 article. More about the Tabors’ years in Leadville can be found in the two-volume series History of Leadville and Lake County, Colorado, available for checkout from the State Publications Library.

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021