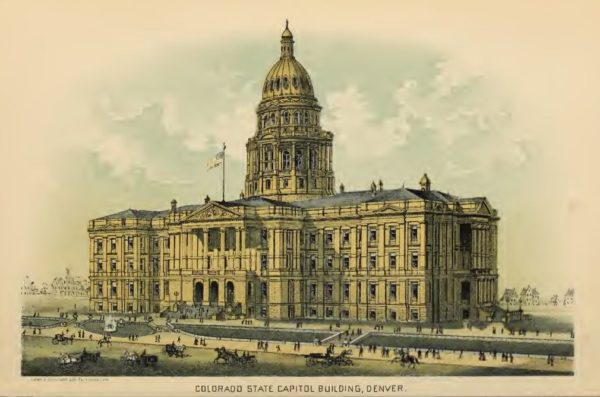

Today, the Capitol Building with its famous gold dome is one of the most recognized symbols of our state. But the road to building a capitol was a long and winding one, fraught with complications that included lawsuits, the firing of the architect, and even uncertainty over whether Denver would remain the state capital. The result, however, is a building that is still regarded as a historical and architectural treasure more than a century later. Now, researchers and anyone interested in the history of the state’s most significant building have online access to significant primary source documents that tell the story of how the Capitol was planned and built.

The United States government established Colorado Territory on February 28, 1861. During the first few years the territorial capital moved around as different towns vied for the honor. Finally, in December 1867, the territorial legislature designated Denver as the capital, and a month later, accepted a gift of ten acres from a Denver landowner named Henry Cordes Brown. The land was to be used as the location for a capitol building.

Brown had traveled extensively before he and his family decided to settle in Denver. After their home was washed away in the 1864 Cherry Creek flood, Brown decided to move to higher ground. He purchased land on a lonely hill southeast of downtown; soon, people began calling the hill “Brown’s Bluff.”

Over the next couple of decades, many Denverites began to look for a place where they could escape the bustle and noise of the rapidly expanding commercial downtown. The idea of having a home near the future Capitol Building had a certain cachet, so many who had made fortunes in mining, banking, and real estate began building their Gilded Age mansions on Brown’s Bluff – soon to be known as Capitol Hill. Yet as the neighborhood grew up around it, the capitol site sat empty.

As Colorado’s attempts at statehood languished, the territory faced difficulty raising money for the new capitol. A construction fund established in 1872 and the creation of a short-lived Board of Capitol Commissioners in 1874 had little effect. Even after statehood was granted in 1876, the lot continued to grow weeds. Part of the problem was the uncertainty over the capital’s location, as Denver competed with leaders from other cities as they tried to capture the seat of state government. Finally, in 1881, a vote of the people made Denver the permanent state capital.

Meanwhile, Brown was losing money. If he hadn’t donated the land, he could have made a fortune selling lots to developers and home builders. In 1879 Brown sued the State to get his land back; after several years of legal battles, which even reached the U.S. Supreme Court, Brown’s claim was finally denied in 1886 and construction on the capitol could proceed in earnest.

Even with the issue tied up in court, state officials began preparations for the construction of a statehouse. In 1883, a law was passed providing funds for the construction of the capitol and establishing a Board of Capitol Managers to provide oversight. The board first met in February 1883, less than two weeks after passage of the bill. By May, they were making an inspection tour of some of the newer capitol buildings in other states. Next, they turned their attention to choosing the proper building stone for the statehouse. In 1884, the board worked closely with experts from the Denver Society of Civil Engineers and the Colorado School of Mines to test numerous rock samples including different varieties of limestone, granite, and sandstone. The board released a detailed analysis of their findings, which can now be viewed online.

Yet there were still many delays. Brown’s lawsuits were still pending, and the board felt that the 1883 legislation was overly restrictive and had not appropriated enough money for the construction. In 1885, new legislation reorganized the Board of Capitol Managers and addressed the board’s actions concerning the legal disputes.

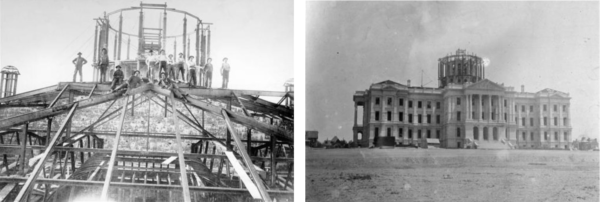

Finally, momentum began to increase. A contest was held for the design of the building, and the board chose architect Elijah Myers, who had designed the statehouses for Michigan and Texas in addition to numerous courthouses and city halls around the country. Myers and the board planned a structure that would combine modern technology with a classical design reminiscent of the United States Capitol. With Brown’s lawsuits now dismissed, ground was finally broken in July of 1886. Yet it wasn’t until 1890 that a ceremony was held to celebrate the laying of the cornerstone, as more delays hampered construction.

Myers and the Board of Capitol Managers soon began to have serious disagreements. Myers’ salary was to be 2.5% of the total building cost. But as his plans for the building grew more complex, explains historian Derek Everett, “some members of the legislature and the board thought that Myers had purposely designed an overly complicated structure to get more money from the state.” Myers was fired in June of 1889; the circumstances are described in detail in the Board’s 1889-90 Biennial Report. Superintendent Peter Gumry took charge of the construction, but was tragically killed in 1895 when a boiler exploded at a hotel he owned on 17th Street.¹ Then, the next superintendent fell into disfavor with the board. Finally, Denver’s leading architect, Frank Edbrooke, who had come in second in the original architectural competition, was appointed to supervise the building’s completion.

The exterior had essentially been finished by 1893, but much interior work remained. The building was opened for occupation in November 1894, with work continuing on the grand staircase, rotunda, and other architectural features. Much discussion was held on who would be the subjects of the Hall of Fame windows, which were installed in 1900. Finally, the building was considered complete in time for the 1901 legislative session. Construction had taken fifteen years, and it had been more than thirty years since Brown had donated the land.

But it wasn’t quite done yet. Work was still being finished on the grounds; additionally, the Capitol had been built with a copper dome, and after just a few years it began to turn greenish and unappealing. In 1908, the copper was replaced by gold, today one of the building’s best known features. And the dome needed something to top it, too. Myers’ original designs had called for an allegorical statue atop the dome, but Edbrooke proposed instead that they install a lighted glass globe, similar to one he had seen a the Pan-American Exposition in 1901. The Board approved the plan, and the traditional architecture of the dome was complemented by this new, modern feature.

Henry Brown died in 1906, and by that time Coloradans, grateful for his gift, had mostly forgotten about the lawsuits. Many came to pay their respects as Brown lay in state in the Capitol after his death. A large portrait of Brown also hangs in the building to this day, and a mini-museum in the dome is known as Mr. Brown’s Attic. The building has undergone many renovations over the century. In recent years, several major projects have included safety enhancements as well as restoration of many of the building’s original architectural features. The work continues to be overseen by today’s version of the board, now known as the Capitol Building Advisory Committee.

The biennial reports of the Board of Capitol Managers for 1883 to 1928 have been digitized and are available online from the State Publications Library. These reports provide a wealth of detail on all aspects of the building’s planning and  construction, including appropriations and expenditures; labor; architectural details; and more.

construction, including appropriations and expenditures; labor; architectural details; and more.

Additional reports, including those from the present-day committee, can be found by searching the library’s online catalog. The collection also includes many other publications about the history, art, and architecture of the State Capitol. For a detailed account, see Everett’s book The Colorado State Capitol: History, Politics, and Preservation (University Press of Colorado, 2005).

¹ The Gumry Hotel explosion claimed 22 lives and injured many others. In addition to Gumry, several others associated with constructing the capitol were also staying at the hotel, including board member Herman Lueders, who escaped and survived. To learn more, see Dick Kreck’s article “The Pit of Horror: Colorado’s Gumry Hotel Catastrophe” in the Summer 1994 issue of Colorado Heritage, available for checkout from the State Publications Library.

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021