Sheer cliffs, deep chasms, and dark shadows make the 2,000-foot-deep Black Canyon of the Gunnison one of Colorado’s most spectacular natural wonders, and twenty years ago, it was officially designated a National Park. Yet for centuries, this sublime canyon has challenged those who wished to conquer it.

Ute Indians were the first to explore and make their homes in Black Canyon area. Evidence has shown, however, that they only lived along the canyon’s rims – not within the inhospitable, steep gorge. Spanish expeditions of the eighteenth century bypassed the canyon. Finally in 1853 a party led by Captain John Gunnison set out to explore the area. A graduate of West Point, Gunnison had been exploring the Utah Territory since 1849. In 1853 Congress sent him on an expedition along the river that would eventually bear his name. (An early account of the expedition can be found in the 1916 publication Historical Sketches of Early Gunnison; the National Parks’ website also provides a history.) Like the Utes before them, however, Gunnison and his men were only able to go so far into the Black Canyon. The expedition continued on into Utah, where Gunnison and several of his men were killed in a Paiute Indian attack. His second-in-command, Lt. E.G. Beckwith, issued the report of the expedition and concluded that a railroad through the canyon would be a difficult and expensive undertaking.

In the early 1880s, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad commissioned surveys of the canyon. They began laying track along the eastern end, in spite of the advice from Beckwith and other previous surveyors. The struggle to build a railroad through the canyon is detailed in the article “Man Against the Black Canyon,” which appeared in the Spring 1973 issue of the Colorado Historical Society’s Colorado Magazine. Railroad surveys would continue in the canyon until 1909, when President Taft presided over the opening of the Gunnison Tunnel. The railroad route can be seen in this 1913 Geologic Map of Colorado.

The coming of the railroad brought tourists to the area. In 1925, Colorado: The Western Slope, a promotional publication from the State Board of Immigration, noted that “[t]he Black canon of the Gunnison river in the western part of [Montrose] county has long been greatly admired by railroad tourists. The Rio Grande Western railroad follows this canon for several miles.” In 1930 an automobile road was constructed to the canyon’s rim; three years later, a portion of the Black Canyon was designated as a National Monument. Colorado Magazine articles from 1934 and 1963 discuss the monument. In 1976, during the height of the environmental movement in Colorado, part of the monument was designated as a Wilderness Area. Finally, in 1999, fourteen miles of the forty-eight mile canyon were designated as Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park.

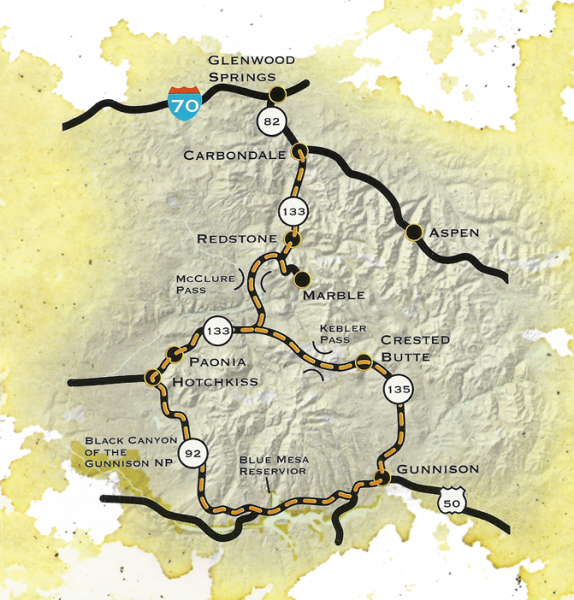

Three years after the change in designation, economists at Colorado State University published a report entitled Economic Impact of National Park Designation of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison on Montrose County, Colorado. They found that designation brought in about 24,000 new visitors to the area. Black Canyon of the Gunnison is also one of the highlights of the West Elk Loop Scenic & Historic Byway. (You can learn about all of Colorado’s Byways in this guide.)

While modern-day visitors may have an easier time than the early explorers, Black Canyon of the Gunnison still provides visitors with awe-inspiring experience.

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021