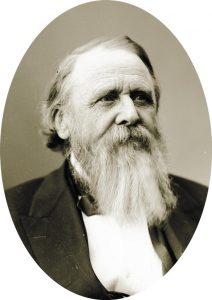

Colorado’s second territorial governor, John Evans, is remembered for his many contributions to the development of Denver, including bringing the railroad to the young town and founding the Colorado Seminary, which became the University of Denver. Evans is also remembered for being disgraced by his role in the Sand Creek Massacre and his subsequent resignation as governor.

Colorado’s second territorial governor, John Evans, is remembered for his many contributions to the development of Denver, including bringing the railroad to the young town and founding the Colorado Seminary, which became the University of Denver. Evans is also remembered for being disgraced by his role in the Sand Creek Massacre and his subsequent resignation as governor.

Originally from Ohio, Evans was a medical doctor who, after moving to Chicago, quickly rose to the top ranks of his field. He helped found Chicago’s Mercy Hospital and Northwestern University (Evanston, Illinois, home of Northwestern, is named for him), founded the Illinois Medical Society, taught at Rush Medical College, and made several innovations in the field of obstetrics. In addition to his medical work, Evans also invested in railroads, which brought him wealth. Evans used his wealth to involve himself in Republican politics and became an avid supporter of Abraham Lincoln. The President showed his gratitude by offering Evans the governorship of Washington Territory, which Evans declined; however, Evans accepted when Lincoln offered Colorado Territory a year later. Evans served as territorial governor from 1862 to 1865.

In Colorado Evans continued his interest in railroads, using his influence to encourage the railroad builders to build to Denver, ensuring that the city would thrive. He also worked with William N. Byers and others to encourage settlement in Colorado. A devout Methodist, Evans got to know Colonel John Chivington, a Methodist minister, through their work in establishing the Colorado Seminary, which was founded in March 1864. That summer, Indian attacks on white settlers and transportation systems caused many to call for their governor to do something to protect civilians. Evans failed to create policy that would bring peace, so in November 1864, while Evans was away in Washington, D.C., Col. Chivington and his Colorado Volunteers attacked a peaceful camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians at Sand Creek. Because most of the victims of the massacre were women, children, and the elderly, Coloradans and Congress alike were indignant, and Governor Evans was forced to resign.*

Although Evans’ political career had ended, his influence in Colorado had not, and until his death in 1897 he continued to be recognized as one of Denver’s leading citizens. He was responsible for finding the financing to bring the Union Pacific Railroad from Cheyenne to Denver in 1870 (Cheyenne being on the Transcontinental Railroad) and continued to serve on the Board of Trustees for both Colorado Seminary and Northwestern University until his death. Today, Mount Evans, Denver’s Evans Avenue, and the city of Evans, Colorado are all named for the governor. Evans’ children were also important in Denver’s history. William G. Evans ran the Denver Tramway Company, Anne Evans helped to found the Denver Art Museum and the Central City Opera, and Josephine Evans married a later Colorado governor, Samuel Elbert.

In our library you can find many resources about Governor Evans, the Evans family, and the Sand Creek Massacre. There is a lengthy bio starting on page 10 in Volume 4 of the Colorado Historical Society’s 1927 History of Colorado. Also, Colorado: A History of the Centennial State (University Press of Colorado, 2005), which can be checked out from our library, covers Evans in depth, particularly regarding his financing of the railroad. Evans is also profiled in several Colorado Magazine and Colorado Heritage articles:

- Regarding Evans’ influence on the railroads, see articles in the Spring 1973 issue.

- For articles on Sand Creek, see the Fall 1964 and Fall 1968 issues.

- To learn about Evans’ role in an early bid for statehood, see the January 1931 issue.

- For biographies of the two Evans first ladies — Evans’ wife, Margaret, and daughter Josephine Evans Elbert — see the January 1962 and October 1962 issues, respectively.

- Issue 4, 1989 of Colorado Heritage explores the history of the Byers and Evans families upon the opening of the Byers-Evans House as a museum. Governor Evans did not live in the 1883 house, but it was home to his descendants.

Finally, Evans’ gubernatorial records and a short bio are available from Colorado State Archives.

*In 2014 Northwestern University, which Evans had founded, undertook a study to determine Evans’ role in the massacre. The study concluded that while “no known evidence indicates that John Evans helped plan the Sand Creek Massacre or had any knowledge of it in advance,” Evans “nonetheless was one of several individuals who, in serving a flawed and poorly implemented federal Indian policy, helped create a situation that made the Sand Creek Massacre possible.” The study continued that after the massacre Evans tried to rationalize and even defend it; and “his recollections of the event displayed complete indifference to the suffering inflicted on Cheyennes and Arapahos.” Therefore, the University concluded that its founder “deserves institutional recognition for his central and indispensable contributions to the establishment of Northwestern and its development through its early decades, but the University has ignored his significant moral failures before and after Sand Creek. This oversight goes against the fundamental purposes of a university and Northwestern’s own best traditions, and it should be corrected.”

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021