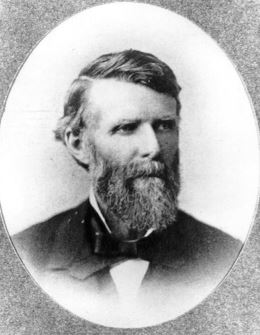

Colorado’s Pitkin County was named for Frederick Walker Pitkin, who served as governor of the state from 1879 to 1883. Born in Connecticut in 1837, Pitkin had settled in Milwaukee until ill health caused him to seek the “climate cure” first in Europe and then out west. He arrived in Colorado’s San Juan region in 1874, and upon regaining his health he opened a law practice and also invested in mining.

Colorado’s Pitkin County was named for Frederick Walker Pitkin, who served as governor of the state from 1879 to 1883. Born in Connecticut in 1837, Pitkin had settled in Milwaukee until ill health caused him to seek the “climate cure” first in Europe and then out west. He arrived in Colorado’s San Juan region in 1874, and upon regaining his health he opened a law practice and also invested in mining.

After just a few years of living in the state, Pitkin, a Republican, ran for and was elected governor of Colorado, succeeding John L. Routt. Although Routt had been elected as Colorado’s first statehood governor, he had also been previously appointed as Territorial Governor. Therefore, Pitkin was the first state governor who had not previously been appointed to the territorial post. Pitkin’s time in office was characterized by several crises, including railroad conflicts, miner’s strikes, and relations with the Ute Indians. The Utes, who had been forced to give up their nomadic hunting traditions and take up farming, rebelled in 1879. In response, Pitkin brought in the militia and had the Utes removed to a reservation in Utah. (To learn more about the history and legacy of the Utes in Colorado, check out The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado and New Mexico from our library or visit History Colorado’s online exhibit, Ute Tribal Paths).

Pitkin won re-election in 1880 (at that time governors served two-year terms). His 1881 address to the legislature, available online from our library, gives his perspective on the “Indian troubles,” the Leadville miners’ strike, and other issues of the day. During his era, Colorado state publications were printed not only in English, but also in German and Spanish. In our library collection you can find a German version of Pitkin’s 1881 inaugural speech as well as a Spanish version of his 1883 address to the legislature, given just before he left office. Our library has also digitized the German version the 1881 session laws.

Governor Pitkin chose not to run again in 1882, instead trying for an open seat in the U.S. Senate, which he lost. After his defeat, he moved to Pueblo where he set up a law practice. He died at age 49 in 1886, leaving behind a wife, Fidelia, and three children.

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021