In the first decades of the twentieth century, Victorian architectural styles gave way to newer styles including Beaux Arts and Mediterranean-influenced architecture. One of the most significant architects in Colorado to embrace these architectural styles was Jules Jacques Benoit Benedict. Although today he is most remembered for his Denver residential designs (many examples can be found in the Denver Country Club and around Cheesman Park), Benedict’s influence extends well beyond his Denver estates.

Jacques Benedict grew up in Chicago and, undoubtedly influenced by the great architects of that city, began practicing there in 1899 before embarking on additional study in Paris, where he attended the famed Ecole de Beaux Arts — considered to be the finest architectural school in the world. After returning to the US he practiced in New York for a time, but saw more opportunity in the West so relocated to Denver in 1909. This was during the height of the City Beautiful Movement in Denver, and among some of Benedict’s first projects in this city were libraries (such as the Woodbury Branch Library in North Denver), schools (such as Park Hill Elementary), and park amenities (such as the Washington Park boating pavilion). He also designed buildings in Boulder, Evergreen, Genesee, Golden, Idaho Springs, Littleton, and Sedalia. One of his only commercial structures was the elegant Central Bank Building at 15th and Arapahoe in downtown Denver, which was torn down in 1990 amidst much controversy; even Denver’s Mayor Peña fought to save it from demolition.

Yet some of Benedict’s most intriguing buildings are the ones that were never built. Can you imagine Denver’s City and County Building as a highrise? Benedict did. In 1926, when the City announced plans for a new municipal building in Civic Center, Benedict submitted a design for a 35-story Gothic Revival skyscraper clearly influenced by Chicago’s famous Tribune Tower. Although the Denver Post rooted for Benedict’s design, Mayor Stapleton and city officials preferred the Neoclassical-style building envisioned by Civic Center Park designer Edward Bennett in 1917. Stapleton hired a team of forty leading architects to carry out the design, and the new City and County Building was completed in 1932.

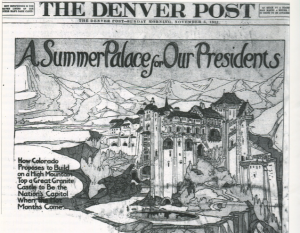

Another of Benedict’s unbuilt buildings is perhaps better known, because hikers pass its cornerstone every day on their way up Mount Falcon in Jefferson County. Benedict was hired by visionary John Brisben Walker as architect for a proposed Summer White House for the President. For a time, Coloradans rallied behind the idea of a Presidential mansion on Mount Falcon; schoolchildren even collected pennies toward funding the construction. Benedict and Walker fought for the idea for ten years, but it was eventually abandoned, and today only Benedict’s cornerstone remains as a reminder. You can find out more about Benedict’s architectural visions in “Architect J. J. B. Benedict And His Magnificent Unbuilt Buildings,” by Dan W. Corson, in the Summer 1997 issue of Colorado Heritage. This issue is available for checkout from our library. Additionally, History Colorado has a list of Benedict’s buildings in their Architects of Colorado database.

The Denver Post was an enthusiastic supporter of both Benedict’s Summer White House (left) and proposed City and County Building (right).

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021