This spring marks the 40th anniversary of the volcanic activity at Mount St. Helens, which culminated in a major eruption on May 18, 1980.

Mount St. Helens, located in Washington state, had experienced some minor eruptions in the early 1800s but had been relatively quiet since 1857. Then in March of 1980, scientists began to notice something was going on when a series of earthquakes started. The earthquake activity continued, with as many as 10,000 small quakes during late March, April, and the beginning of May. The first phreatic (steam) eruption of the volcano occurred on March 27, and smaller eruptions continued on and off over the next month and a half.

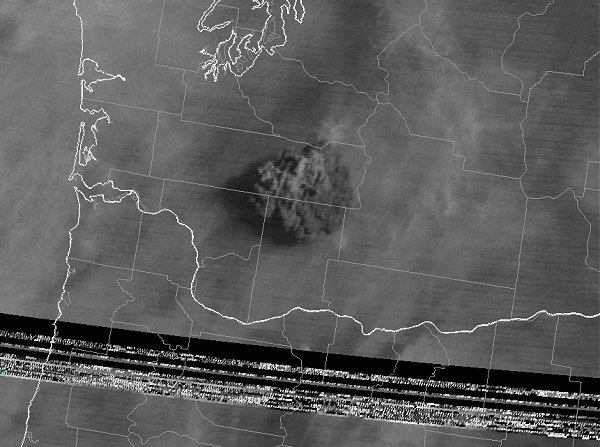

On the morning of May 18, geologists’ measurements were consistent with readings from the past month. Nothing seemed much different from the previous days and weeks. Then, at 8:32 a.m, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake on the north slope of the volcano triggered a massive landslide – said to be the largest landslide in recorded history – which sent rubble careening more than 13 miles. The landslide caused pressure changes in the magma and volcanic gas that resulted in a huge lateral blast a few seconds later. The flow of rock, ash, steam, and lava destroyed about 230 square miles of forest, and a second, vertical blast sent a column of ash 15 miles (80,000 feet) into the air. Strong winds carried an estimated 540 million tons of ash for hundreds of miles, to states as far away as Colorado. My dad remembers leaving for work Monday morning and finding a half-inch thick layer of gray ash covering his car, which he had to brush off like snow.

Because the May 18 eruption had occurred almost without warning, there were still many people in the vicinity of the volcano, even though Washington had declared a disaster emergency in April and many had evacuated. Still, the volcano caused the deaths of at least fifty-seven people, including several scientists and professional photographers.

The eruption set off mudslides, forest fires, and other reactions. 200 houses were destroyed, along with 47 bridges and 185 miles of roadway. With transportation cut off in many places, communities faced difficulty receiving assistance. It was estimated that the eruption caused more than $1 billion in damage. A few small eruptions continued over the next six months, and over the years, periods of activity at the still-active volcano have been recorded. Someday, it will erupt again.

Aside from ash falling in Colorado, what is our state’s connection to Mount St. Helens? Following the disaster, the University of Colorado’s Natural Hazards Research and Applications Information Center (known today simply as the Natural Hazards Center) published several studies on the eruption. They include Emergency Planning Implications of Local Governments’ Responses to Mount St. Helens, which looked at how local government emergency operations responded to the ash fallout near the volcano; and Emergency Response to Mount St. Helens’ Eruption, which examined the response during the early phase of volcanic activity in March and April, including how emergency managers assessed the risk of a major eruption. These studies are available online from our library; another publication, Four Communities Under Ash After Mount St. Helens, is available for checkout in print.

Sources:

https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/st_helens/st_helens_geo_hist_99.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1980_eruption_of_Mount_St._Helens

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021