Colorado’s only third-party governor, Davis Waite, was elected in 1892 as a member of the Populist Party. In the era of progressive reforms and worker unrest, Populists advocated “an eight-hour workday, employees’ liability legislation, a child labor law, and state operation of coal mines.”1 Populism swept Colorado that year, with 57% of Colorado voters backing Populist presidential candidate James Weaver. In addition to electing Waite as governor, Colorado also sent thirty-nine Populists to the State Legislature. Waite is often remembered for the nickname given him by his opponents — “Bloody Bridles” Waite. The sobriquet came from one of Waite’s speeches, where he declared that it was “better that blood should flow to the horses’ bridles, than our national liberties be destroyed.”

The Populists’ day was short, however. The following year, 1893, Colorado and the nation suffered an enormous financial panic that left as many as 45,000 Coloradans out of work. In the 1894 election (at that time governors served two-year terms), Waite was easily unseated by Republican Albert W. McIntire, who decried Waite’s support of labor unions and progressive reforms. The nail in the coffin of Waite’s governorship, however, was what has come to be known as the City Hall War.

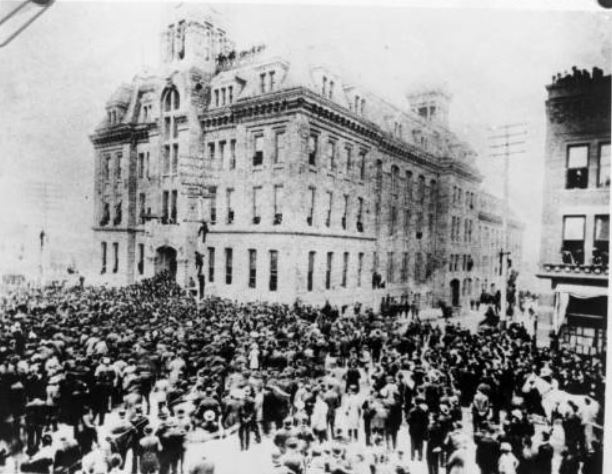

At that time, the governor had the authority to appoint members of the Denver Fire and Police Board, which had been created by the Legislature in 1891. When two of Waite’s appointees did not, in his opinion, do enough to suppress vice in Denver, he ordered them to step down. Disagreeing with the governor about their effectiveness, the two appointees refused to resign and barricaded themselves inside City Hall. In response, Waite ordered the Colorado militia to forcibly remove the two men. County sheriffs and Denver police, along with a contingent of shady characters led by Soapy Smith, posted armed guards at the building to protect the board members. Everyone wondered which side would fire first. Fortunately, it never came to that. A group of leading Denver citizens, including newspaperman William Byers and railroad baron David Moffat, convinced Waite to take the matter to the state Supreme Court instead. The court ruled that while the governor did have the authority to remove the board members, he did not have the authority to order in the National Guard for that purpose. In the end, the incident brought embarrassment to the city and crushed Waite’s popularity.

In his final address as governor, available online from our library, Waite had no apologies for his actions in the City Hall War, claiming that his appointees had profited from blackmail. “This practice of blackmail has been by no means confined to the city of Denver…it prevails in New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and nearly all the principal cities of the country, to such an extent that municipal corruption has become a national disgrace.” (It was around this same time that Theodore Roosevelt began instituting reforms in his role as police commissioner in New York). Waite defended his actions by saying — in his customary hyperbole — that “I had rather die a thousand deaths than to allow a single prerogative that constitutionally belongs to my office, to be taken away while I am governor.” Waite’s narrative of the City Hall War, on pages 45-51 of the address, provides a fascinating firsthand account of the incident. Waite’s letter to the Colorado National Guard is also reprinted in the document: “I can enforce the laws, but not without great bloodshed. As governor of the state I call on you to assist me in preserving order and preventing bloodshed.”

The document also contains the inaugural address of the new governor, Albert McIntire: “On assuming the duties of the chief executive office of the state, it cannot be out of place for me to call attention to the meaning and intention of the people…that the law is to be impartially administered and enforced, regardless of so-called class, condition or party affiliation; and that the supremacy of the law is to be maintained at all hazards” — a direct jab at his predecessor.

For more governor’s speeches and other resources, search our online catalog.

1 Abbott, Carl, Stephen J. Leonard, and Thomas J. Noel, Colorado: A History of the Centennial State, University Press of Colorado, 2005. Available for checkout from the State Publications Library.

Photos courtesy Colorado State Archives and Denver Public Library Western History Department.

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021