With Thanksgiving kicking off this year’s holiday season, it’s time for many Coloradans to turn their kitchens into bakeries. But Colorado’s altitude can present a problem for holiday baking – have you ever followed your Midwestern grandma’s cookie recipe perfectly, only to end with burnt cookie crisps? Or tried a cake recipe that is delicious in Denver but is completely dry in Leadville?

According to the Colorado State University Extension, any elevation above 3,000 feet (so, all of Colorado) can impact cooking and baking for a few reasons. First, air pressure is lower at higher altitudes, meaning that yeast and leaveners react with more force and cause baked goods to rise and fall more quickly. Second, liquids evaporate faster at higher altitudes, causing sugar to become more concentrated, baked goods to stick to their pans, and results of dry, crumbly cakes.

Luckily for Colorado’s bakers, CSU Extension home economics scientists have been studying high-altitude baking for decades and many of their guides and recipes are available in our digital repository!

One of the pioneers of high-altitude recipe testing was Inga Allison, whose name and influence can be found in many of the Extension’s early high-altitude baking guides. The recipe conversion tips found in these publications are still relevant today:

- Baking flour mixtures at high altitude (1930)

- Baking quick breads and cakes at high altitude (1932)

- Baking angel food cake at any altitude (1935)

- Preparing and baking sponge cake at different altitudes (1940)

The Extension’s later baking guides are also chock full of useful baking advice and recipes with adjustments included for altitudes of 5,000, 7,500, and 10,000 feet:

- Cookies recipes from a basic mix for high altitudes (1992)

- Quick mixes for high-altitude baking (1992)

- High altitude baking (1992) – this book contains a recipe for chocolate mashed potato cake!

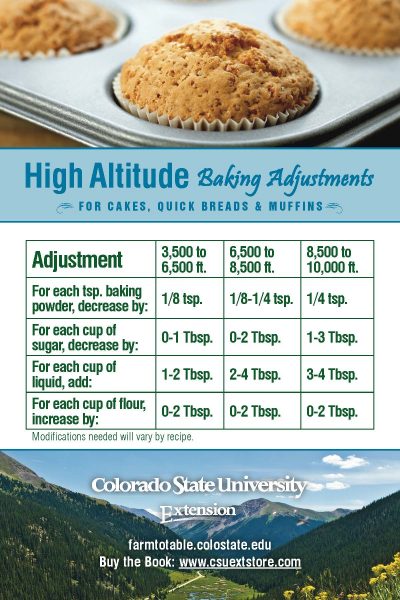

For quick recipe adjustments during your winter baking frenzy, the CSU Extension’s High Altitude Baking Adjustments chart (below) is a handy guide:

Happy baking!

- Celebrating Colorado’s immigrant heritage - June 27, 2025

- Colorado’s Scenic and Historic Byways: Guanella Pass - June 6, 2025

- Who is protecting Colorado’s pollinators? - May 16, 2025