When you wake up, one of the first things you might do is open your weather app to see what the temperature is and if it’s supposed to rain that day. You then use that information—or data—to make important decisions, like what to wear and whether you should bring an umbrella when you go out. The fact is, we are all collecting data every day—and we use that data to inform what we do next.

It’s no different in libraries. We collect data about circulation, program attendance, the demographics of our community, and so on. When we collect the data in a formalized way and use it to make decisions, we call this evaluation. Simply put, “evaluation determines the merit, worth, or value of things,” according to evaluation expert Michael Scriven.

Equitable Evaluation

So what does this have to do with equity, diversity, and inclusion? Well…everything. If evaluation does in fact determine the merit, worth, or value of programs and services, what happens when your library’s evaluation excludes or overlooks certain groups from the data? Let’s take a look:

You are trying to evaluate patron satisfaction at your library, so you print off a stack of surveys and leave them on the lending desk for patrons to take. While everyone in your target audience may have equal access to the survey (or in other words, are being treated the same), they don’t all have equitable access. Sometimes people may need differing treatment in order to make their opportunities the same as others. In this case, how would someone who has a visual impairment be able to take a printed survey? What about someone who doesn’t speak English? These patrons would likely ignore your survey, and without demographic questions on language and disability, the omission of these identities might never be known. Upon analyzing your data, conclusions might be made to suggest, “X% of patrons felt this way about x, y, and z.” In reality, your results wouldn’t represent all patrons—only sighted, English-speaking patrons.

Inequities are perpetuated by evaluation when we fail to ensure our methods are inclusive and representative of everyone in our target group. The data will produce conclusions that amplify the experiences and perspectives of the dominating voice while simultaneously reproducing the idea that their narrative is representative of the entire population. Individuals who have historically been excluded will continue to be erased from our data and the overarching narrative, serving to maintain current power structures.

Evaluation With the Community, not On the Community

That’s a heavy burden to take on as an evaluator and a library professional, especially when taking part in people’s marginalization is the last thing you would want to do. Luckily, the research community has long been working on some answers to this problem. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is contingent on the participation of those you are evaluating (your target population) and emphasizes democratization of the process. CBPR is defined as:

“focusing on social, structural, and physical environmental inequities through active involvement of community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process. Partners contribute their expertise to enhance understanding of a given phenomenon and integrate the knowledge gained with action to benefit the community involved.”

CBPR centers around seven key principles:

- Recognizes community as a unit of identity

- Builds on strengths and resources

- Facilitates collaborative partnerships in all phases of the research

- Integrates knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners

- Promotes a co-learning and empowering process that attends to social inequalities

- Involves a cyclical and iterative process

- Disseminates findings and knowledge gained to all partners

As one librarian put it, CBPR “dismantles the idea that the researcher is the expert and centers the knowledge of the community members.” When those that you are evaluating (whether it be patrons, non-users, people with a disability, non-English speakers, etc.) are involved in the entire process, your data will invariably become more equitable. As a result, your evaluation outcome will more effectively address real problems for your community. It’s a win-win for everyone.

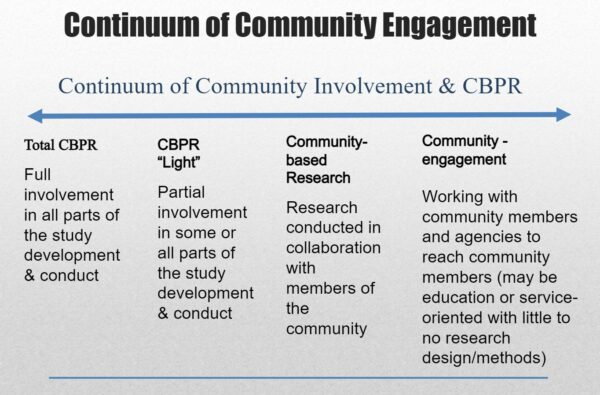

However, if diving into a full community-based participation evaluation feels impossible given your time and resources, it’s okay. Think of CBPR as your ideal and then adjust to a level that is feasible for your library. The continuum of community engagement below outlines what some of those different levels might look like.

The Big Takeaway

Evaluating your practices, policies, and programs in a library can lead to better outcomes for your library community. However, even the best of intentions can create harm for historically underrepresented groups when they are excluded from the very data used to make decisions that impact them. When undertaking an evaluation of any kind, think about the principles of CBPR and how you can incorporate them into your plan.

- Nothing About Us, Without Us - August 4, 2021

- Being an Ally: What it Means and How to Do it - July 9, 2021

- If Not Now, Then When? Starting your EDI process - June 7, 2021